In recent years, many leaders in the nonprofit landscape have taken important steps to incorporate diversity and inclusion into their organizations’ missions and practices. As nonprofits work with an increasingly diverse and globalized set of clients, beneficiaries, partners, and employees, many have engaged in thoughtful self-examination and made changes to ensure they engage effectively and communicate respectfully across any number of cultural barriers. Universities and independent schools may have offices or deans of multicultural education to advance the diversity and inclusivity of their student and faculty bodies. Many hospitals provide initiatives to help doctors better care for a wide cultural spectrum of patients and their families.

Yet how frequently are similar cultural considerations made in nonprofit fundraising? The landscape of philanthropy is also quickly diversifying , and many CCS clients work with constituents from a broad range of racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds: from multiethnic Catholic parishes, to hospitals serving predominantly immigrant communities, to museums that increasingly partner with art collectors from mainland China and Hong Kong.

Developing cultural competence is essential to building trust and effective engagement with an increasingly diverse community of donors. It goes beyond making simple generalizations about people of different backgrounds; rather, it challenges professionals to deeply understand their donors’ mindsets and adapt their practices accordingly. Doing so will allow nonprofit fundraisers to build better relationships, expand their organizations’ reach, and more effectively and respectfully engage with philanthropists and donors from varied walks of life on their own terms.

What is Cultural Competence?

In order to fundraise effectively through a multicultural lens, it’s helpful for nonprofits to first understand the multiplicity of cultures that their supporters may identify with. When we hear the word “culture,” we may jump to considering national origin or ethnicity. These are certainly important cultural elements, but they aren’t the only ones. Culture – what social psychologist Geert Hofstede calls “the programming of the mind” – can account for how many different groups of people act, think and communicate. Age, socioeconomic status, religion, race, sexual orientation, nationality, and gender are all cultural factors to consider in fundraising, and (to complicate matters further) each person has several intersecting cultural identities. Families from Germany and China might approach giving to nonprofits very differently, but so might 35-year-old donors and 70-year-old donors, or Orthodox or Secular Jewish philanthropists. Before developing donor strategies, it’s critical for nonprofits to understand any significant groups within their supporter base that share a similar culture or identity.

Once fundraisers have identified their supporters’ cultural identities, they can use cultural competence to translate that information into a lens by which to effectively understand and relate to donors. Cultural competence is the ability to think and function effectively across cultures and work effectively with people from different backgrounds.[1] It can encompass awareness of one’s own and others’ “mental programming” and developing practical knowledge of how that programming will translate into everyday situations.

Applying Cultural Competence to Nonprofit Fundraising

Many nonprofit fundraisers already know their supporters’ cultures well and are cognizant of the best way to approach them. Fundraisers for Catholic churches have found that Vietnamese parishioners frequently prefer to give collectively rather than individually; others have noted that many Latino congregations center their fundraising around community-focused events rather than individual solicitations. Yet there are always ways to deepen and broaden one’s cultural awareness. Cultural factors to consider in working with donors can include:

• Language. What primary language do your constituents and donor base speak? Would they feel more comfortable speaking or receiving materials in their native language, or are their English-language skills a point of pride?

• Religion and spirituality. Religion can heavily impact a donor’s relationship to giving. Many cultures view giving as a religious activity and may prioritize gifts to their church, mosque, synagogue, or temple. Fundraisers should be aware of how religion influences a donor’s motivation, but also how religious observances might influence when and how to best discuss a gift. It’s important to be considerate of major holidays like Yom Kippur, when observant Jewish donors may consider it improper to discuss finances, or Ramadan, when Muslim donors may be fatigued or feel uncomfortable attending events with food as they fast. When planning events, fundraisers should also consider dietary restrictions.

• Age. Studies of generational giving demonstrate that a donor’s age can influence how, where, when, and why they choose to give. For instance, while 60% of donors over 75 contribute to religious causes, only 32% of Millennials aged 24-42 do the same. Age contributes to what people value in communication with an organization as well. For example, younger donors may gravitate toward online giving not only for its convenience, but also because they value reducing the paper use of traditional appeal and thank-you mailings.

• Nationality and ethnicity. Often the most common cultural miscommunications occur between people of different nationalities – people who may have grown up surrounded by norms, values, and unspoken assumptions that create just as much trouble as a language barrier. This can happen with fundraising as well. One independent school fundraiser spent many fruitless attempts to meet with his school’s Korean parent community, only to have them turn down all his meeting requests. He finally learned from a colleague that many parents were actually very interested in supporting the school, but felt uncomfortable because he’d asked to meet with them at home – an extremely intimate setting for Korean nationals. Once he began setting up meetings in bars and restaurants, he found parents were willing and excited to speak with him. Nonprofit fundraisers should make an effort to understand how national culture affects donors’ communication preferences, assumptions around philanthropy, and decision-making processes. In many cultures, the gender of the donor and fundraiser may also play a key role in how (or even if) meetings take place, who becomes involved in “charity work,” and who controls family finances. Yet while these can be deep and important considerations to make, small touches, like remembering to send good wishes to a donor on important cultural holidays, can also make people feel meaningfully seen and appreciated.

• Socioeconomic and educational factors. Finally, a donors’ educational and class background can also determine their approach to philanthropy – or even if they consider philanthropy something exclusively for “other people” with traditionally wealthy backgrounds. Written appeals that sound too formal or complex may come off as elitist to some donors, and organizations may need to put extra effort into engaging donors from backgrounds where giving was neither a possibility nor a priority. Nonprofits should reflect on how they conduct donor education and cultivation, and how they can share the impact of gifts of every size.

Developing Cultural Competence

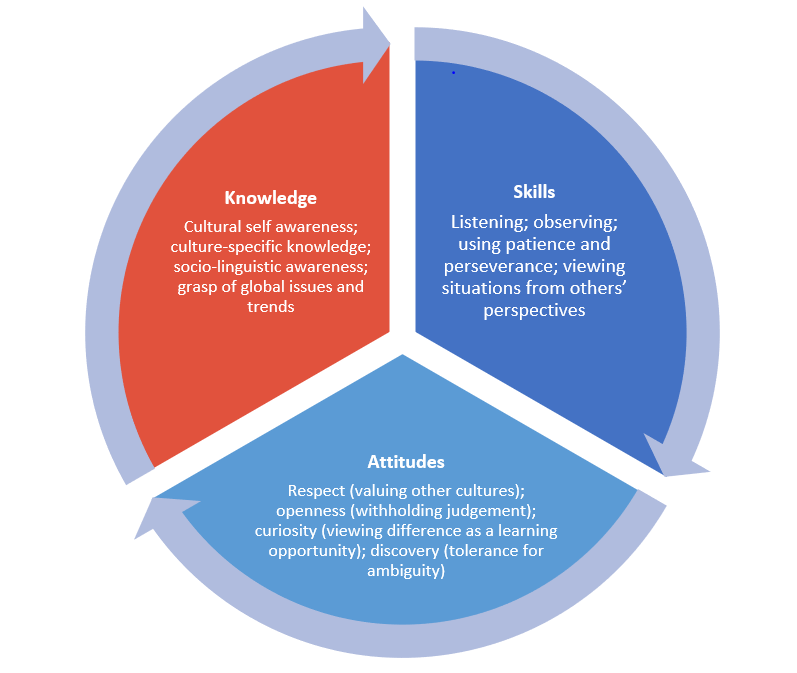

So how can fundraisers build their cultural competence, avoid cross-cultural mishaps, and engage donors from a wide range of backgrounds? It may be tempting to hunt for easy rules of thumb or generalizations, but cultures and identities are incredibly complex and intersecting. Even two donors of the same ethnicity and religion might have wildly different personalities or value sets. Rather than make generalizations (“Latinos always put family first”) or hunt for resources that skim the cultural surface (“10 Tricks for Working with Businesspeople from X!”), fundraisers should look for ways to incorporate a culturally competent mindset into all their work. Cultural scholar Debra Deardorff[2] recommends building this mindset through a three-pillared “Knowledge, Skills, Attitudes” approach:

Developing the first pillar – cultural knowledge – might mean learning a language or developing expertise in a specific regional culture or religion, by spending time abroad, or attending services. Knowledge also implies cultural self-awareness, built by examining one’s own biases and assumptions. This examination often reveals that much of what seems “normal” or “common sense” may actually be determined by one’s own specific upbringing.

Of course, cultural knowledge is only useful if it’s effectively put into practice with other people. To do so, fundraisers need the second pillar of cultural competence – skills of listening and asking questions, thoughtful empathy, and the ability to work through conflicts and miscommunications. All of this should be undergirded with an open mind, a willingness to learn and be flexible, and a sense of comfort in unfamiliar or ambiguous situations where there may not be one clear “right approach.”

Deardorff’s model demonstrates a holistic approach to cultural competence, and all of these pillars can be incorporated through small changes in our mindset and daily work to have a big impact. Fundraisers can start with an attitude of willingness to learn over the long term, coupled with the humility that it’s not possible to quickly become fully competent in someone else’s culture. From there, they can:

• Reflect. Begin by reflecting as a department or organization to understand – what cultures and identities are represented in our donor body? In our staff? What are our own biases and assumptions that might be based on our cultural background? Do fundraising volunteers seem similar to the people they’re speaking with? Are we making decisions because they’re right for all our donors, or because it’s what we’re used to?

• Ask. Don’t be afraid to ask the right person to understand a complex or unfamiliar cultural situation. That person may be an organizational colleague, a board member or, in some cases, the donor themselves.

• Empathize. Everyone has their own assumptions of what’s normal. In working with donors, consider what actions might seem best from their perspective (which you should have an inkling of, if you’ve reflected and asked the right questions!). Ask, “how might we meet this individual where they are in with their approach and understanding of philanthropy?”

• Learn. In addition to reaching out to ask questions, there are many ways to learn about the history and context of the cultures your donors are a part of. Engage in conversation and ask people where and how you might learn more. If you’re interested specifically in developing your professional cultural competence skills in fundraising, the following resources are helpful:

– Lilya Wagner, Diversity and Philanthropy: Expanding the Circle of Giving

– Urvashi Vaid and Ashindi Maxton, The Apparitional Donor: Understanding and Engaging High Net Worth Donors of Color

– Related CCS Fundraising Articles:

- https://ccsfundraising.com/taking-the-first-steps-to-reaching-diverse-catholic-communities/

- https://ccsfundraising.com/building-a-culture-of-philanthropy-in-independent-schools/

- https://ccsfundraising.com/adapting-new-generation-parent-donors/

- https://ccsfundraising.com/a-guide-to-engaging-immigrant-catholics-and-ethnic-parishes-in-capital-campaigns/

Lasting Effects

Adapting a lens of cultural competency in fundraising will promote understanding through respectful intercultural dialogue. Ultimately, fundraisers with cultural competence will also be more empathetic, supportive, and understanding of the people they work with, regardless of background. Donors who feel authentically seen, heard, and understood will be excited to partner with an organization that allows them to do so on their own cultural terms.

[1] Adapted from Leung, K., Ang, S. and Tan, M.L. (2014), ‘Intercultural Competence’, Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behaviour, 1:4889-519.

[2] Deardorff, D. K. (2006), The Identification and Assessment of Intercultural Competence as a Student Outcome of Internationalization at Institutions of Higher Education in the United States, Journal of Studies in International Education 10:241-266.

CCS Fundraising is a strategic fundraising consulting firm that partners with nonprofits for transformational change. Members of the CCS team are highly experienced and knowledgeable across sectors, disciplines, and regions. With offices throughout the United States and the world, our unique, customized approach provides each client with an embedded team member for the duration of the engagement. To access our full suite of perspectives, publications, and reports, visit our insights page. To learn more about CCS Fundraising’s suite of services, click here.